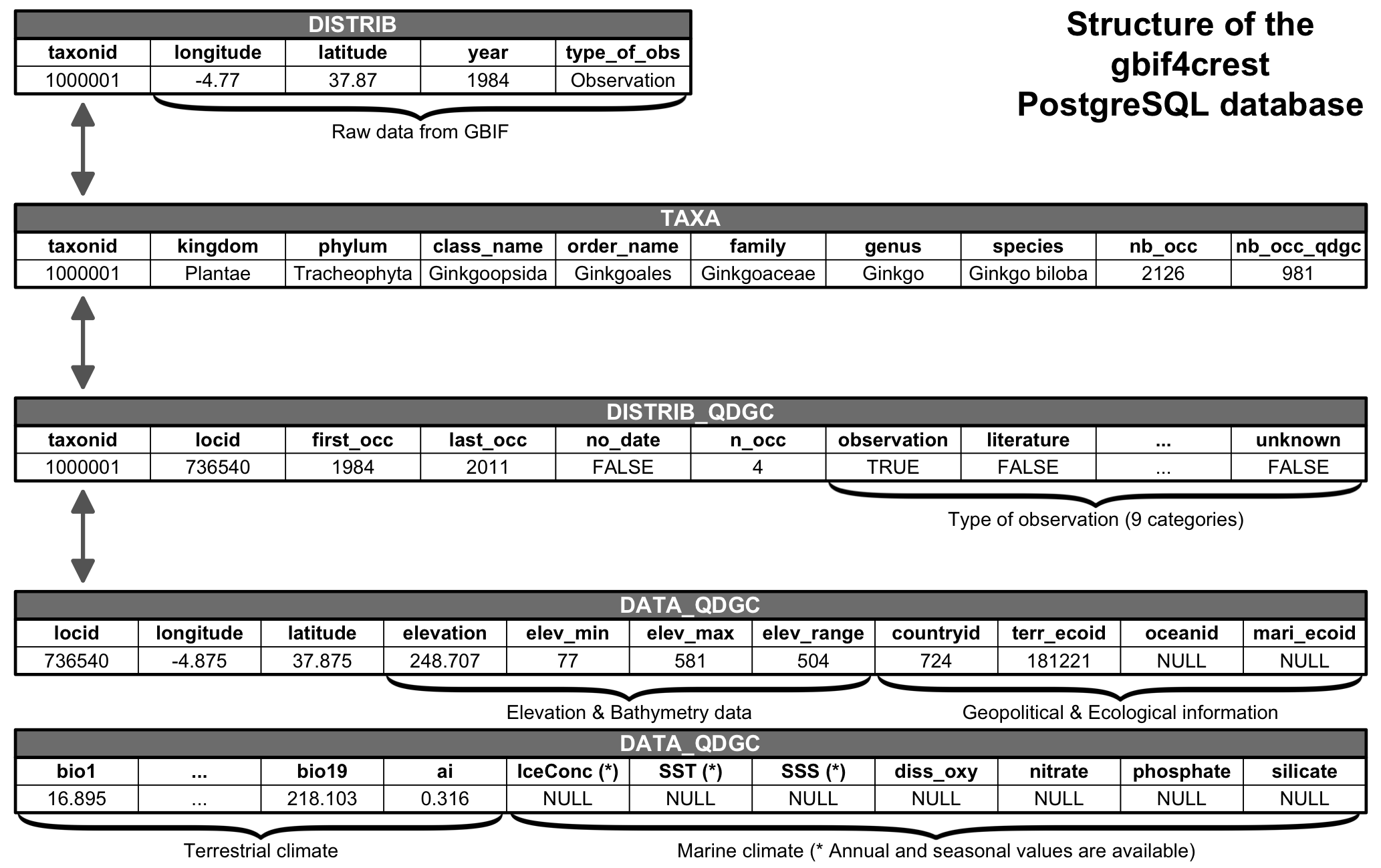

Source of the calibration data

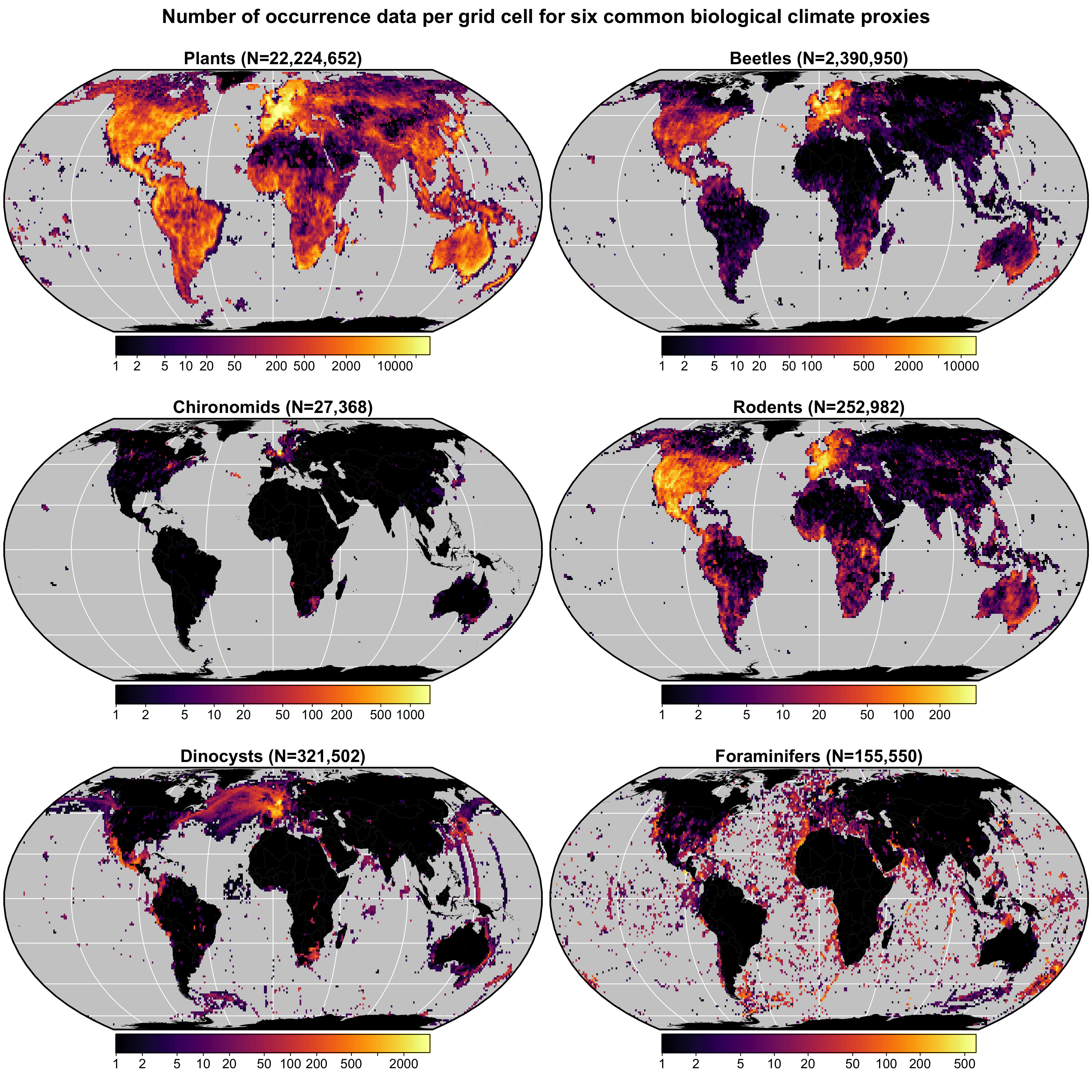

A multiproxy calibration dataset to estimate PDFs from a global collection of geolocalised presence-only data (hereafter proxy distributions) was first presented in [1]. These data were obtained from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) database, an online collection of geolocalised observations of biological entities. The calibration dataset (hereafter gbif4crest) contains the species distributions of six common palaeoecological fossil: the five taxa presented in the original version of the dataset — plants [2-12] for fossil pollen and macrofossils, chironomids [13], beetles [14], diatoms [15] and foraminifera [16] – to which rodents [17] were recently added (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Data density of the six climate proxies available in the gbif4crest calibration database. The total number of unique species occurrences (N) is indicated for each proxy. The maps are based on the ‘Equal Earth’ map projection to better account for the relative sizes of the different continents.

The coordinates of all the presence records of these six common

palaeoecological fossil proxies were upscaled at a spatial resolution of

0.25 x 0.25° (hereafter QDGC for Quarter-Degree Grid Cell) and

subsequently associated with terrestrial and oceanic environmental

variables at the same resolution [18-24] (see details in Table 1).

The QDGC spatial resolution is an empirical trade-off between numerous

factors, including the resolution of the presence data, the quality of

the data or the spatial representativity of the studied proxy. However,

this tradeoff may be suboptimal in some situations, and for that reason,

crestr can also be used with the raw GBIF data and even

alternative calibration datasets.

In its current version (V2), the gbif4crest calibration

dataset contains about 25.3 million unique presence data for the six

proxies. Unfortunately, the density of available data varies strongly

between proxies and regions (Fig. 1). Plant data

dominate the calibration dataset (>22 million unique occurrences) and

allow for the use of crestr across all landmasses where

vegetation currently grows. For the five other proxies, the datasets are

still incomplete in many regions, restricting the use of

crestr (e.g. chironomids). However, these datasets

are regularly updated by GBIF. For example, the first version of the

gbif4crest dataset released in 2018 contained about 17.5

million QDGC entries, but the new version presented here contains nearly

25.3 million entries (~44% increase). The range of ‘reconstructible’

areas is thus rapidly broadening (see, for instance, the coverage of

Russia by plant data compared to the first version of the

gbif4crest dataset [1].

Table 1 List of terrestrial and marine variables available in the gbif4crest database. Each one can be selected in crestr using its associated code. List of abbreviations: (Temp.) Temperature, (Precip.) Precipitation, (SST) Sea Surface Temperature, (SSS) Sea Surface Salinity.

| Code | Full name | Source |

|---|---|---|

| bio1 | Mean Annual Temp. (°C) | [18] |

| bio2 | Mean Diurnal Range (°C) | [18] |

| bio3 | Isothermality (x100) | [18] |

| bio4 | Temp. Seasonality (standard deviation x100) (°C) | [18] |

| bio5 | Max Temp. of the Warmest Month (°C) | [18] |

| bio6 | Min Temp. of the Coldest Month (°C) | [18] |

| bio7 | Temp. Annual Range (°C) | [18] |

| bio8 | Mean Temp. of the Wettest Quarter (°C) | [18] |

| bio9 | Mean Temp. of the Driest Quarter (°C) | [18] |

| bio10 | Mean Temp. of the Warmest Quarter (°C) | [18] |

| bio11 | Mean Temp. of the Coldest Quarter (°C) | [18] |

| bio12 | Annual precip. (mm) | [18] |

| bio13 | Precip. of the Wettest Month (mm) | [18] |

| bio14 | Precip. of the Driest Month (mm) | [18] |

| bio15 | Precip. Seasonality (Coefficient of Variation) (mm) | [18] |

| bio16 | Precip. of the Wettest Quarter (mm) | [18] |

| bio17 | Precip. of the Driest Quarter (mm) | [18] |

| bio18 | Precip. of the Warmest Quarter (mm) | [18] |

| bio19 | Precip. of the Coldest Quarter (mm) | [18] |

| ai | Aridity Index (unitless) | [19] |

| sst_ann | Mean Annual SST (°C) | [20] |

| sst_jfm | Mean Winter SST (°C) | [20] |

| sst_amj | Mean Spring SST (°C) | [20] |

| sst_jas | Mean Summer SST (°C) | [20] |

| sst_ond | Mean Fall SST (°C) | [20] |

| sss_ann | Mean Annual SSS (PSU) | [21] |

| sss_jfm | Mean Winter SSS (PSU) | [21] |

| sss_amj | Mean Spring SSS (PSU) | [21] |

| sss_jas | Mean Summer SSS (PSU) | [21] |

| sss_ond | Mean Fall SSS (PSU) | [21] |

| diss_oxy | Dissolved Oxygen Concentration (mol/L) | [22] |

| nitrate | Nitrate Concentration (mol/L) | [23] |

| phosphate | Phosphate Concentration (mol/L) | [23] |

| silicate | Silicate Concentration (mol/L) | [23] |

| icec_ann | Mean Annual Sea Ice Concentration (%) | [24] |

| icec_jfm | Mean Winter Sea Ice Concentration (%) | [24] |

| icec_amj | Mean Spring Sea Ice Concentration (%) | [24] |

| icec_jas | Mean Summer Ice Concentration (%) | [24] |

| icec_ond | Mean Fall Sea Ice Concentration (%) | [24] |